by Julie Dodd

Women’s History Month is an excellent time to celebrate Anne May Davis, “the founding mother” of Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP).

Even if you are a regular visitor to GSMNP, you may not know of her role in the creation of the park.

That was true of me. In years of visiting Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I hadn’t been aware of the role of Anne May Davis and her husband, W.P. Davis, in creating the national park. That led me to want to learn about Anne May Davis and share her story.

My research included reading GSMNP websites about the history of the park and Women of the Smokies, articles from The Knoxville Sentinel archives, census data, and magazine articles and blog posts on the park’s history, a graduate thesis, and history websites.

This blog post provides a condensed story of Anne May Davis and Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

In her 2012 thesis, “Great Women of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park: Defining Nature and the National Park Service,” Rachel Lanier Roberts wrote:

“Despite her significant role in the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Davis is largely overlooked in historical literature. In most accounts she is simply described as the park’s ‘mother.’”

Anne May Davis played a critical role in initiating the idea of a national park in the Smokies.

What is omitted in describing her role is that she generated essential support for the park in the Knoxville business community. As an elected representative in the Tennessee Legislature, she sponsored the legislation needed to purchase land to establish the park and worked to get the legislation passed.

Anne May Davis’ background

Anne May, born on Dec. 27, 1875, grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, in a prosperous family and graduated from Bryn Mawr College, at a time when women typically did not attend college.

In 1902, she married Willis Perkins (W.P.) Davis, an industrialist and 16 years her senior. Her wedding announcement in the Louisville Courier-Journal in Jan. 12, 1902, described her as “one of the most charming and cultivated girls in Louisville society. She is an active worker at the cathedral and in philanthropic as well as church work.”

Anne and W.P. Davis move to Knoxville

In 1915, the couple and their two daughters moved to Knoxville. In addition to being manager of the Knoxville Iron Works Company, W.P. Davis served on the Board of Directors of the Knoxville Automobile Club and the Knoxville Chamber of Commerce.

The couple’s involvement in the community led to her becoming a friend of Knoxville Mayor Ben Morton.

In “Knoxville’s Legacy to the Smokies,” Fred Brown described Anne and W. P. Davis’ arrival in Knoxville:

“A force to be reckoned with Anne Davis and her industrialist husband, Willis P. Davis, arrived in Knoxville in 1915 from Louisville, KY. Willis Davis took over Knoxville Iron Co. and became a leading civic power in the community. He was also well connected to influential Washington politicians. At a time when women were viewed as ornaments, dressed in long, cumbersome dresses, hats with large feathers and elbow-length gloves, Anne Davis was a rebel.“

Anne Davis served in the Knoxville Garden Club. According to researcher Rachel Lanier Roberts, prominent women of that era used Garden Clubs to promote conservation and environmental issues in their communities.

The Davises frequently visited the Smokies. In addition to enjoying the beauty of the mountains, they recognized the potential of the Smokies promoting tourism and business for the communities near the mountains, including Knoxville.

Idea for creating a national park – 1923

The couple visited Yellowstone National Park in the summer of 1923. On their train ride back to Knoxville, Anne Davis shared her idea of creating a national park in the Smokies.

She recalled the conversation with her husband in a letter, written in 1952, to the Secretary of the Smoky Mountains Conservation Association, Russell Hanlon:

“We have seen some beautiful country. Grand mountains but nothing more majestic than our own great Smokies. Why should there be national parks in the West and only one tiny one (Arcadia [sic] in Maine) in the east? Mr. Davis replied, ‘If that is the way you feel about it, I will see what I can do.’”

Inspired by his wife’s idea, he began talking with Knoxville business leaders about creating a national park in the Smokies. He promoted the park, being near to Knoxville, as a way of increasing economic growth for the city.

Building support for a national park – 1924

The couple helped found the organization that became the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association (GSMCA), an organization created by the Knoxville Automobile Club. GSMCA’s goal was to help establish a national park in the Smokies. W.P. Davis was elected GSMCA’s chairman.

GSMCA presented their proposal of the Smokies being selected to be a national park to Dr. Hubert Work, U.S. Secretary of the Interior. By this time, many other groups were lobbying for the creation of a national park in their area of Southern Appalachia. U.S. Secretary Work established the Southern Appalachian National Park Committee to study some 30 areas.

When the Southern Appalachian National Park Committee was to visit Asheville, North Carolina, W.P. Davis worked to get an invitation to the meeting. A nine-person delegation from Knoxville traveled to Asheville and met with the committee on July 30, 1924. Part of their presentation to the committee included showing photographs of the Smokies in Tennessee taken by brothers Jim and Robin Thompson.

The photographs were so striking that two members of the committee hiked to Mt. Le Conte to view the area. They were so impressed with what they saw. The Tennessee portion of the Smokies became a candidate for a new national park.

W.P. Davis wrote hundreds of letters to influential people to promote the idea of the Smokies becoming a national park, including inviting President Calvin Coolidge to have a summer vacation in the Smokies.

Election to Tennessee House of Representatives – 1925

In order for the Tennessee section of the Smokies to be included in the new national park, Tennessee had to purchase the land. In the fall of 1924, the purchase of the land stalled in the Tennessee legislature.

That led Anne Davis to run for an open seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1925, a decision that surprised her husband. With the support of Knoxville Mayor Ben Morton, she won the election.

Her election came less than five years after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, granting the right to vote to American women. Anne Davis was only the third woman ever elected to the Tennessee State Legislature.

“I have never been interested in politics just for the sake of playing the political game but I have always been interested in women and their advancement along all lines,” she was quoted in a 1925 Knoxville newspaper article. “… I saw in this a way to make an opening for the women of my section of Tennessee in state politics” and called for more women to be elected to the state legislature.

In the article, Anne Davis was quoted as saying she was “very much interested in getting the National park for this section (East Tennessee).”

The political battle in Tennessee over creating a national park was between those who wanted a national park established and those who wanted a national forest that could be logged by timber companies. At the time, 18 lumber companies owned 85 percent of the land that would become the park.

Anne Davis and Mayor Morton convinced Col. W.B. Townsend, owner of Little River Lumber Company, to sell his 78,000 acres of land to the state.

Sponsoring and promoting the legislation

Anne Davis pushed for the legislation to purchase the land from the Little River Lumber Company. When the purchase was opposed by legislators who said they had heard the acreage was “stump land,” she arranged a trip for the entire legislature to visit the Smokies for an inspection. The beauty of the Smokies convinced most that Tennessee should purchase the land to create a national park.

Anne Davis worked with Knoxville Mayor Ben Morton and Colonel David Chapman, chairman of the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association and representative to the Tennessee state Park and Forestry Commission, to convince Knoxville’s City Council to pay one-third the cost of the land as a way to promote business and tourism in the Knoxville area.

In “Knoxville’s Legacy to the Smokies,” Fred Taylor described the negotiating: “Without Knoxville’s forward-thinking Mayor Ben Morton, an irrepressible activist named Anne Davis, and a satchel of Knoxville taxpayer money, there would be no park today.”

The Senate passed the bill but it failed in the House by two votes. Governor Peay rallied the members of the house, emphasizing the purchase would only be made if Congress agreed to create a national park.

The House passed the bill April 9, 1925.

Gov. Peay signed the bill, using a pen with an ostrich feather. He then presented the pen to Representative Anne Davis as recognition of her role in passing of the bill.

That land became “the first large parcel of land set aside for the creation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park,” according to GSMNP’s website on Women of the Smokies.

Having achieved her goal of establishing a national park in the Smokies, Anne Davis did not seek re-election.

Mountain and ridge named to honor W.P. and Anne Davis

Following her husband’s untimely death in 1931, Anne Davis moved to Gatlinburg to be closer to the mountains she loved. She established the Gatlinburg Garden Club and was active in the League of Women Voters.

Ann Davis attended the formal dedication of Great Smoky Mountains National Park on Sept. 2, 1940. President Franklin Roosevelt spoke from the Rockefeller Memorial at Newfound Gap at the Tennessee-North Carolina state line.

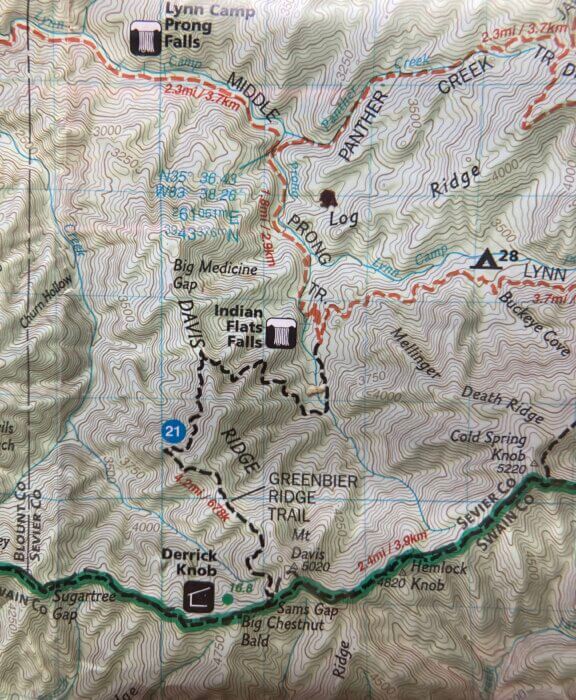

According to the Great Smoky Mountains Association’s “Hiking Trails of the Smokies,” Anne Davis asked the Park Service to name a peak in honor of her husband for his efforts to create Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

The trail guide states: “The Park Service felt so strongly about the Davises’ devotion to the park idea that they named (Mt. Davis) for Willis and the ridge which climbs to it for Anne.”

The Park Service renamed Greenbrier Ridge to be Davis Ridge in honor of Anne May Davis. I now realize Greenbrier Trail, which I hiked as a Girl Scout, runs along Davis Ridge.

Anne Davis lived in Gatlinburg until her death in 1957 at the age of 81.

You can see portraits of Anne and W.P. Davis and the famous ostrich feather pen used to sign the legislation in the GSMNP Park Headquarters in Gatlinburg.

You can see the impact of Anne Davis’ vision and political action any time you visit Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Thanks to GSMNP Librarian-Archivist Michael Aday for providing photographs and documents from the Park’s archives and from the Open Parks Network,