by Holly Jones, Director of Community Outreach & Strategy at Friends of the Smokies

Throughout the 25-year history of Friends of the Smokies, our members have supported the restoration of brook trout to streams in Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP) including Sams Creek and Lynn Camp Prong.

Although I knew that fisheries programs were one of the many natural resource conservation initiatives funded by our donors’ dollars, I never put much thought into exactly how the Park’s fisheries biologists actually get native brook trout from one stream into another.

Logistics of transporting native brook trout

The logistical considerations are immense. I recently had the opportunity to witness firsthand some creative problem-solving by the Smokies’ Matt Kulp, Supervisory Fisheries Biologist; Caleb Abramson, Fisheries Technician; and Danny Gibson, animal wrangler for the Facilities Management Division.

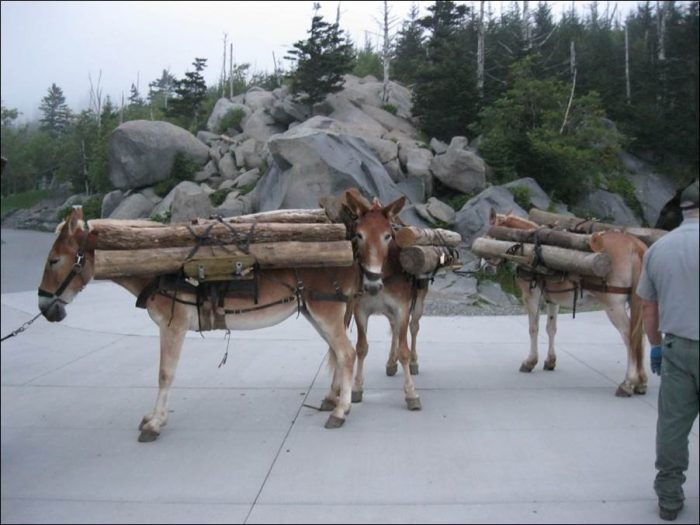

Whatever I might have imagined about how brook trout restoration works, I never anticipated that it could involve mules, and until June 27th it didn’t, at least not in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. According to Fishery Technician Caleb Abramson, the park’s fisheries crew knew that mules had been used in other places to move trout, but it had never been tried in the Smokies.

Perhaps I should explain that the mules involved actually belong to the National Park Service, and they have been a tremendous help in many ways to the men and women they work alongside.

Mules have been assets to the Trails Forever crew throughout the two-year rehabilitation project on Rainbow Falls Trail and also helped with the overhaul of Forney Ridge and Alum Cave Trails. Their home is near Oconaluftee Visitors Center.

On this day, members of the fisheries crew were joined by seasonal Park employees.

They started early from the Deep Creek Trailhead off of Newfound Gap Road (US 441) and hiked down 1.25 miles to access the stream.

There they left the mules and their handlers to patiently wait while they broke into two groups heading in opposite directions to collect approximately 125 native brook trout per group.

In order to accomplish efficiently catching the trout, the team members used electronic backpack units to emit a charge into the water that temporarily stunned the fish into a state of suspended animation.

Mules carry trout in portable plastic tanks

Then they transferred the 250 trout into small portable plastic tanks outfitted with aerators to circulate the water and provide sufficient oxygen to sustain them. Those tanks were loaded onto the mules, and the mules and their handlers packed the fish back uphill to the trailhead.

The fishing and packing portion of the day took about 4 hours.

Because mules, and Park employees for that matter, are much stronger uphill hikers than I am, I met them all at the Deep Creek trailhead along with my friend (and GSMNP Volunteer) Regina Kinton. I didn’t want to miss the next stage of the trouts’ adventure.

Reg and I actually took shelter in the truck with Matt Kulp while we waited on the mules to arrive since a strong thunderstorm “walked” its way down US 441 to soak everyone involved.

When Caleb Abramson, the fisheries team, and the animal packers got there with the mules and the fish, they quickly poured the small tanks into a larger tank on Matt’s truck. That tank held water that Matt sourced from Kanati Fork.

Trout are very vulnerable to sudden temperature changes, so moving them into water that came from a colder high elevation environment, like the stream where they had been living, was critical to their viability.

We said “goodbye” to the mules and thanked them for their hard work.

Trout carried in backpack tanks

The final leg of the journey was driving the fish to the Anthony Creek Trailhead, where the fisheries crew transferred the trout back into the small backpack tanks to prepare for their release. Wildlife seasonal intern Tsali Franklin estimated that each tank weighed about 50 pounds.

Trout splash-activated

Just as another thunderstorm hit, we hiked a short way up Anthony Creek Trail where three Park employees carefully “splash-activated” the trout by slowly introducing some of the water from Anthony Creek into the tanks before the brookies were freed into the swift-moving water.

All 250 brook trout successfully made the transition to their new home, joining other native brookies who were relocated there in 2017.

Regina and I hiked together back out to the Cades Cove Picnic area, grateful for the chance to be involved in the first-ever mule-assisted trout restoration in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

To learn more about the Park’s mule team and handler Danny Gibson, check out this excellent article from Smoky Mountain News.