by Julie Dodd

As a visitor to Great Smoky Mountains National Park, you know the value of interpretive signs in the Park, those signs located at cabins and along trails to help you learn about the people who lived in the area or the plants and wildlife.

The “African American Experience in the Smokies: Making the Invisible, Visible” project, in its fifth year, is now at the point of adding new interpretive signs (wayside panels) to tell the stories of African Americans.

For four years, the project staff and partners, which include Friends of the Smokies, have conducted research into the history of African Americans in the Park and surrounding areas.

Archives and libraries were searched. Oral history interviews were conducted. Town hall meetings were held to share their results and ask for community involvement in finding stories and artifacts. With information compiled, the next step is sharing it.

“We’ve met with the resource education staff of the Smokies, who will start infusing these stories into the history of the park,” said Antoine Fletcher, director of the program and science communicator of the Appalachian Highlands Science Learning Center at Purchase Knob.

“These stories add value to our Park – not to discount any other stories but to make the Park more well-rounded,” Fletcher said.

Fletcher has worked for the National Park Service for 15 years, including Russell Cave National Monument, Fort Sumpter National Park, Waco Mammoth National Monument and Lyndon B. Johnson Historical Park. Atalaya Dorfield, from the Greening Youth Foundation, is the project’s research assistant.

Wayside panels of African American Experience in the Smokies

Five interpretive signs will be installed initially in different locations throughout the Park to tell the stories of African Americans.

Job Conservation Corps – sign to be located at Tremont

A Job Corps site operated at Tremont, which is now the Great Smoky Mountains Institute, from 1965-1969. The majority of the 100-man corps were African Americans. The corpsmen completed building construction, trailwork, roadwork and landscaping at Tremont and rehabilitated the campground at Cades Cove.

Daniel White – sign to be located at the Appalachian Trail, Newfound Gap

Daniel “The Blackalachian” White thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail in 2017. “He wasn’t the first African American to finish the trail, but he was from Asheville,” Fletcher said. The project is recognizing both the history of African Americans who lived in the area that now is the Park and current African Americans who live in areas surrounding the Park. White was one of 1,138 to complete the AT in 2017. Only 19 percent of thru-hikers completed the AT that year.

Enloe Enslaved Cemetery – sign to be located at the cemetery near Mingus Mill

The Enloe Enslaved Cemetery, located near Mingus Mill, is the burial site of enslaved people. Fletcher explained that people who happen upon the cemetery, which is only a hundred yards from the parking lot for Mingus Mill, often don’t recognize that it is a cemetery because the graves are small mounds marked by small stones. The sign will identify the area as a cemetery and explain the research involved in studying the cemetery. Friends of the Smokies funded the use of ground-penetrating radar to examine the cemetery without disrupting the gravesites. (More on the cemetery in a future blog post.)

Charles Mingus Jr. – sign to be located at Mingus Mill

Charles Mingus Jr. (1922-1979) is considered one of the greatest jazz musicians and composers of all times, with a career spanning three decades and collaborations with jazz musicians Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. A sign will be installed at Mingus Mill, where his father, Charles Mingus Sr., grew up.

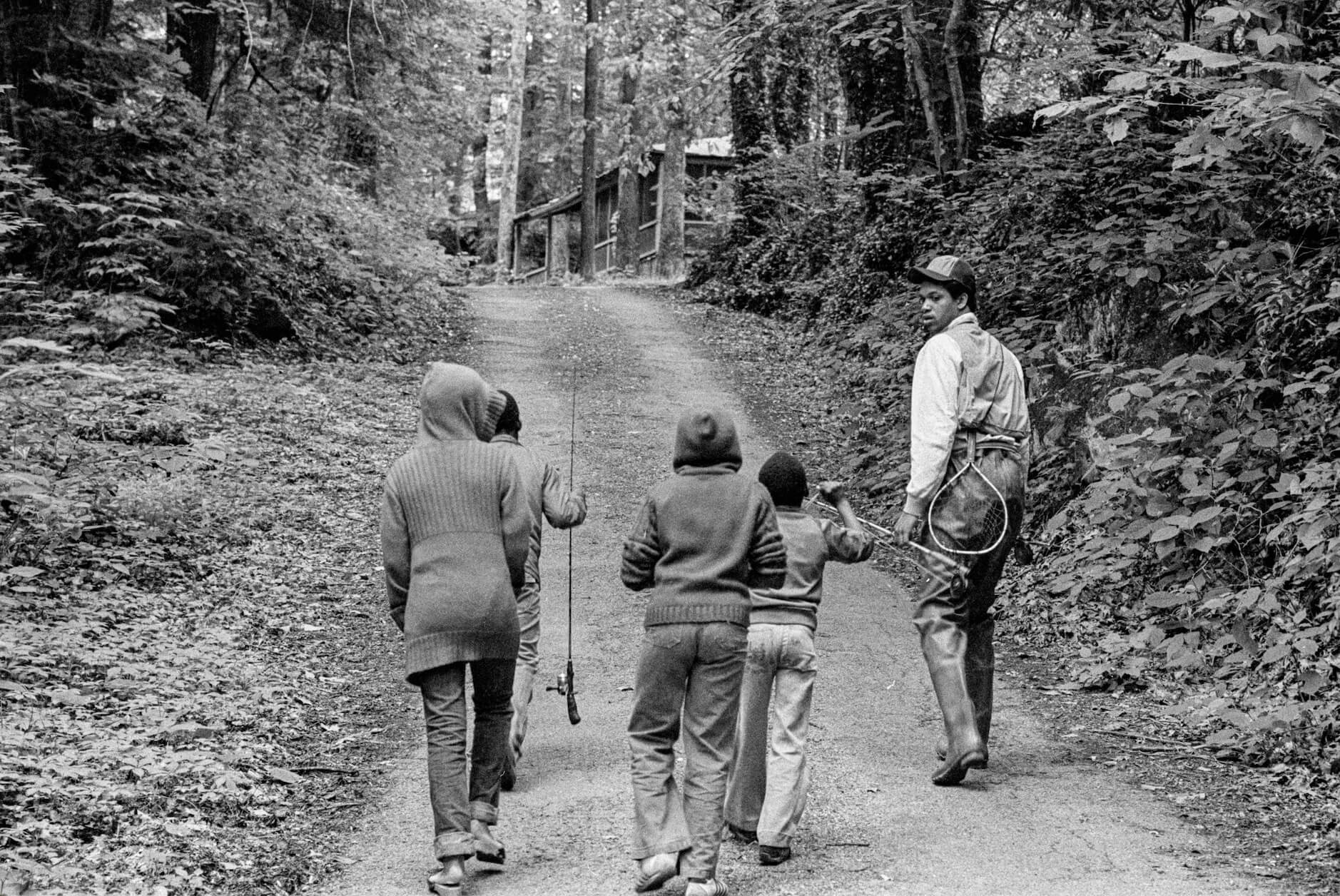

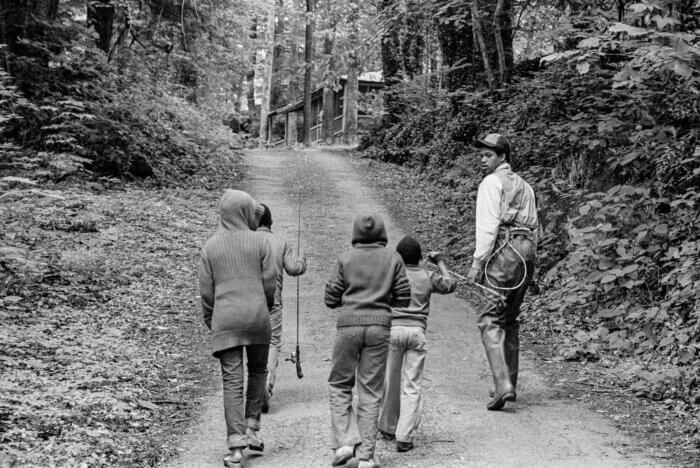

Ron Davis Sr. – sign to be located at Jakes Creek Trail in Elkmont

The cottages at Elkmont were mountain holiday retreats for the wealthy. Ron Davis Sr. and his family helped prepare the Mebane cottage on Millionaire Row in Elkmont, before the Mebane family came in for the weekend or summer.

Stories will be shared in many ways

“A lot of research has to be done and synthesized to create each small but very important story,” Fletcher said.

The extensive documentation is edited into individual two-page articles on various topics and people. The article is then condensed into a 100-word description that will “engage” the readers of the wayside panels.

Fletcher said historical or commemorative metal markers located in cities and along roadsides often don’t attract readers because they contain hundreds of words. Having concise and compelling writing for the wayside panels in GSMNP is important to encourage visitors to read the wayside panels.

Fletcher said that everything collected in the research process will be used in many different ways.

The results of the research will be used to educate park visitors, partners, and staff through teacher workshops, interpretive programs and products and digital media. The oral histories become part of the National Park Service’s national database of oral histories.

Challenges of gathering stories and photographs

Once the 100-word narrative is completed, the story is combined with visuals to create a panel that conveys part of the African American Experience in the Smokies.

Fletcher said that he and Dorfield are exploring library and university archives to locate old photographs. They also are working with people in area communities to obtain photographs and other visuals to help tell the story — and that process can have impediments.

“Sometimes you get the photos and let people know you need signed releases to use the photo but don’t hear back,” Fletcher said, noting that he will drive to pick up those signed releases.

Sometimes people are hesitant to share their family stories or photographs.

“They are skeptical because no one has reached out before,” Fletcher said. “‘Why do people care about our experiences now?’ they ask.”

Fletcher emphasizes the importance of getting each story.

“Once that voice is lost, it’s lost,” he said.

Contribute to African American Experience in the Smokies

If you would like to share stories or artifacts, contact Antoine Fletcher through the African American Experience in the Smokies website.