by Julie Dodd

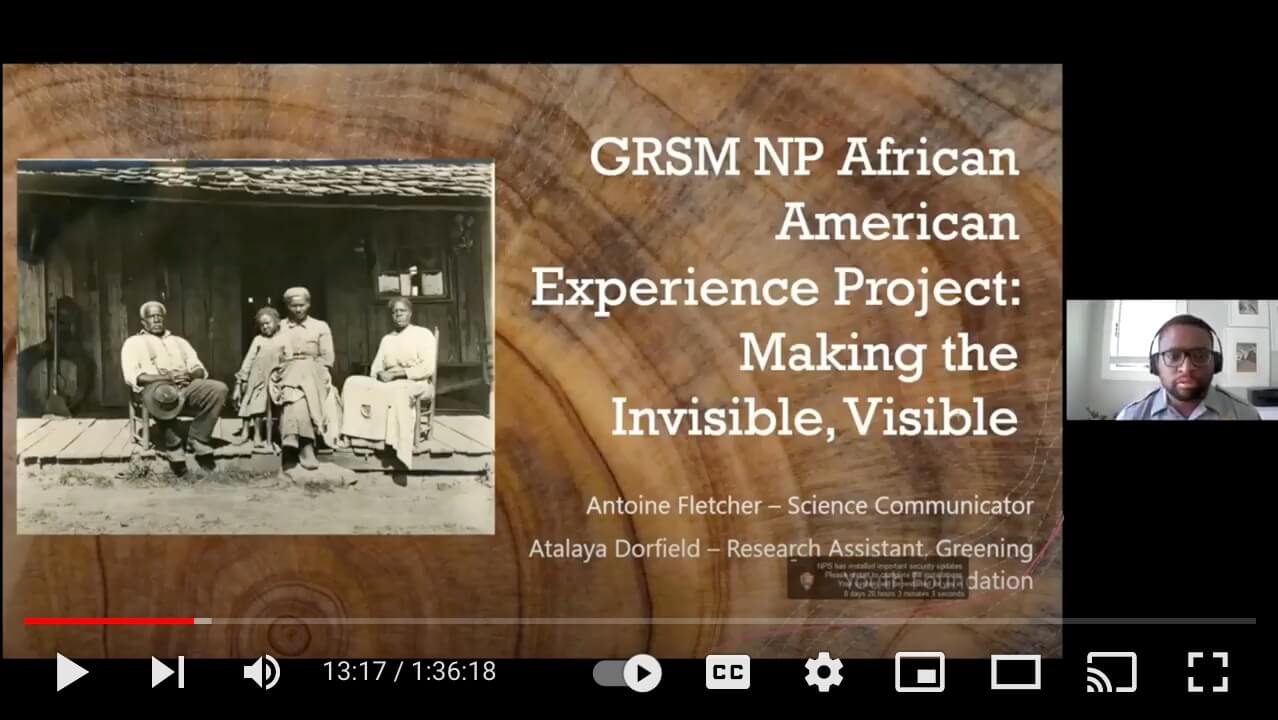

The African American Experience in the Smokies project is moving into its fifth year and has added a subtitle to the project’s name – Making the Invisible, Visible.

That subtitle reflects the findings of the project’s research – African Americans have long been a part of the Smokies. Now the stories of African Americans will be added to the stories the Park tells of Native Americans and white settlers who lived in the Park.

“The process of the project is intensive and extensive,” said Antoine Fletcher, science communicator for the Appalachian Highlands Science Learning Center at Purchase Knob who coordinates the project.

The project is a collaboration between the Park and communities surrounding the Park to document and share the stories of African Americans in the Smokies.

Fletcher has worked with the National Park System for 15 years and joined the staff at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the summer of 2020. His duties also include supervising the Blue Ridge Parkway, Big South Fork Recreation Area, Obed Wild and Scenic River, and Appalachian Inventory and Monitoring Network.

Fletcher previously has served at Russell Cave National Monument, Fort Sumpter National Park, Waco Mammoth National Monument and Lyndon B. Johnson Historical Park. In each location, Fletcher, who is an anthropologist, has been involved in telling the history of the location and the people, animals and plants of the area.

Atalaya Dorfield, from the Greening Youth Foundation, is the research assistant for the project. Dorfield, a native of Charlotte, North Carolina, studied West African culture as an undergraduate at the University of North Carolina/Charlotte, and earned a master’s degree in Black British Writing at Goldsmiths, University of London. She has studied the African Diaspora, the mass dispersion of people from Africa during the slave trades from the 1500s to the 1800s.

In their work on the project, Fletcher and Dorfield have conducted historical research of African Americans in the Smokies, going back to the 1600s with the arrival of slave ships to American and moving forward to the present time. They have recorded oral histories and participated in community gatherings to share their findings and promote interest in the project.

Community presentations

Speaking at community gatherings has been a way for Fletcher and Dorfield to share what they have learned and to encourage others to contribute to the stories of African Americans in the Smokies.

“There are a lot of people doing the work of telling the stories,” Fletcher said. “We want to facilitate that by bringing those people together.”

Last summer, Fletcher and Dorfield spoke to an online meeting of the East Tennessee Historical Society about the project. The recording of the presentation is posted online. A screen capture from the presentation is at the top of the blog post.

Fletcher and Dorfield held three online town hall meetings last fall, hosted by Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, University of North Carolina-Asheville and Western Carolina University.

Recording oral histories

As part of telling the story of African Americans in the Smokies, Fletcher and Dorfield have completed ten oral histories.

“We prefer to do oral histories in person rather than by phone,” Fletcher said, “but sometimes people are hesitant of the technology used to record them or we needed to do the interview on the phone because of COVID.”

Fletcher said the project has been able to connect with Western Carolina University, which has conducted Black oral history interviews and has expanded a course to include doing transcripts of the oral history interviews.

“Oral histories are so important to our research because they provide us with first-hand accounts, stories and histories that we can preserve and share with present and future audiences,” Dorfield explained.

“Key components of conducting an oral history are being intentional with the questions that we ask the interviewee and creating a safe space for them to share their story,” she said. “It is best to allow the interviewee’s responses to flow and for the conversation to take on its own organic shape. That’s how we get the best stories.”

Ann Miller Woodford

One of the oral histories is of Ann Miller Woodford, an artist, author and speaker who lives in Asheville. Miller Woodford grew up in Andrews, North Carolina, and attended the segregated, one-room Colored/Negro Elementary School. Her teacher Ida Mae Logan recognized Miller Woodford’s artistic ability and submitted her artwork to art competitions. Receiving art awards led to Miller Woodford’s decision to be an artist.

“Ann Miller Woodford’s work as both an artist and historian highlights the presence and contributions of African Americans in far western North Carolina, a group that has been left out of the storytelling of that region,” said Dorfield, who conducted the oral history of Miller Woodford.

“Having grown up in Andrews, North Carolina, Ann Miller Woodford’s familial history and personal experiences have expanded the project’s knowledge of African American life and communities in the area,” Dorfield said.

“She aims to ‘make the invisible, visible,’ a goal that the African American Experience project shares as we work to bring visibility to the African American history, culture and people in and around the Smokies.”

Dr. Dennis Branch

Dr. Dennis Branch (1886 -1964) is another subject of an oral history. Branch was a doctor in Newport, Tennessee, a community at that time he lived there had a 2 percent Black population.

Born in Riley, North Carolina, Branch grew up during the Reconstruction Period and always wanted to be a doctor, Fletcher said. Branch earned his medical degree in 1914 from the University of West Tennessee (a historically Black college in Memphis that no longer exists), paying his way through college by being a Pullman porter on trains.

Branch opened a pharmacy in Newport and treated both Black and white patients. In additional to his medical skills as a physician, Branch knew how to use of plants and fungi, following traditional healing methods.

In addition to his medical work, Branch was principal of Newport Consolidated School (an African American school) and was a member of the Newport Rescue Squad. A documentary was made about Branch’s life, and he was featured in 1958 on the TV show “This Is Your Life.” Compiling an oral history of Branch has involved interviews with people who knew him.

“Dr. Branch was not only a doctor but a pillar of the community,” Fletcher said. The community appreciated him for recognizing the tough financial situation for many of his patients and accepting payment in eggs or other goods rather than monetary payment.

“According to residents in Newport, Dr. Branch ate his lunch alone in his office because he couldn’t go into restaurants with his colleagues,” Fletcher said, explaining the Jim Crow segregation laws during Branch’s life. “That had to be very difficult.”

Oral history process

Completing the interview is not the end of the oral history process. Fletcher explained that the interviews have to be transcribed and then transmitted to the National Park Service regional office in Atlanta, which then submits the oral histories to the database used by the NPS.

Support for project

“Funds from Friends of the Smokies and the Great Smoky Mountains Association are so important for the project,” Fletcher said.

Fletcher said the project also has been aided by many people and organizations, including: Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, Blount County (TN) Library, University of North Carolina-Asheville, Western Carolina University, Ron Davis Sr., and Michael Aday – librarian/archivist at the NPS Collections Preservation Center in Townsend.

Future posts will share more about the project’s efforts and how the Park will be sharing the stories that have been collected.

Contact Antoine Fletcher if you have stories, photographs or artifacts to share.