by Julie Dodd

Five new interpretive signs are adding to the storytelling of the African Americans in the Smokies.

The signs – also called wayside panels – will be located in North Carolina and Tennessee and tell the stories of individuals or events connected to their locations.

- Job Conservation Corps – Tremont Institute Center (Old Job Corps Site)

- Daniel White “The Blackalachian” – Newfound Gap Trail Area

- Enloe Slave Cemetery – Mingus Mill

- The Black Mingus Family – Mingus Mill

- The History of the Davis Family – Elkmont

The process of creating one sign can take an entire year to complete, explained Ranger Antoine Fletcher, science communicator for the Appalachian Highlands Science Learning Center at Purchase Knob and coordinator of the African Americans in the Smokies project.

Determining the story to tell

“The process of creating a sign starts with thinking about the stories that are tied to the landscape. Wayside panels should be tied to the landscape to give people the best idea of what happened in a certain time period,” Fletcher said.

“Next, we think about the story. That involves determining the most appealing story or an untold story that is right under our noses,” he said.

Finding those stories has involved hosting group conversations with individuals who live in gateway communities to the Park.

Those conversations were held during in-person community meetings and in town hall meetings held via Zoom, hosted by Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, Western North Carolina University, and the University of North Carolina-Asheville.

“Once we pick the story, we start the research and writing process,” Fletcher said.

Research and writing

The research involved conducting oral history interviews and reviewing hundreds of documents. Fletcher, an anthropologist, was assisted by Atalaya Dorfield, who served as research assistant for the project.

Once the history was written, the story then had to be condensed to fit on a wayside panel.

“The writing process for the wayside panel can be difficult because you have to distill down maybe eight pages of history to about 200 words,” Fletcher said. “Most people read wayside panels for about 30 to 45 seconds. So, you have to capture their minds and hearts in a short amount of time.”

Community involvement in the process

Again, the gateway communities were involved in creating the final story.

“Once we write, we bring a team together to constantly edit, and then another team to work with community members to see what they think and if we are hitting the mark on what we are trying to portray,” Fletcher said.

“We met with community members from Tennessee and North Carolina last year to talk about the wayside panels,” he said. “The project was received well, and we learned a lot, too. One thing that our community members would love to see is more stories about Black women in the park. This has been very difficult, because we have a limited number of stories when it comes to Black women in the Park, but we have been working on this and hope to add more stories about Black women in the future.”

The next step for the creation of the signs was determining visuals to be included on each panel.

“Sometimes getting visuals is hard because of the limited history that we are dealing with,” Fletcher explained. “The Great Smoky Mountains Association helps us create images, or we get permission from libraries to use visuals,” he said.

Installation and the ‘reveal’

All the panels are finished, except for the Black Mingus Family panel. Next, the signs will be installed.

“Installation is where we work with maintenance and cultural resource management to ensure that are selected the right spot that will not unearth any archeological objects,” Fletcher said.

The final phase of the project will be to host a special “reveal” for each panel.

“We are working with the community to have choirs or special VIPS that were part of the project to be there during the reveal of each panel,” Fletcher said.

The signs are just one part of how these stories are being shared.

“Interpretive signs are like icebergs, we give the public just enough information – about 10 percent of the full story — or so that the public will learn from the sign,” Fletcher said. “But the other 90 percent can be used in other mediums, such as websites or educational programs. This helps keep the information fresh for the public.”

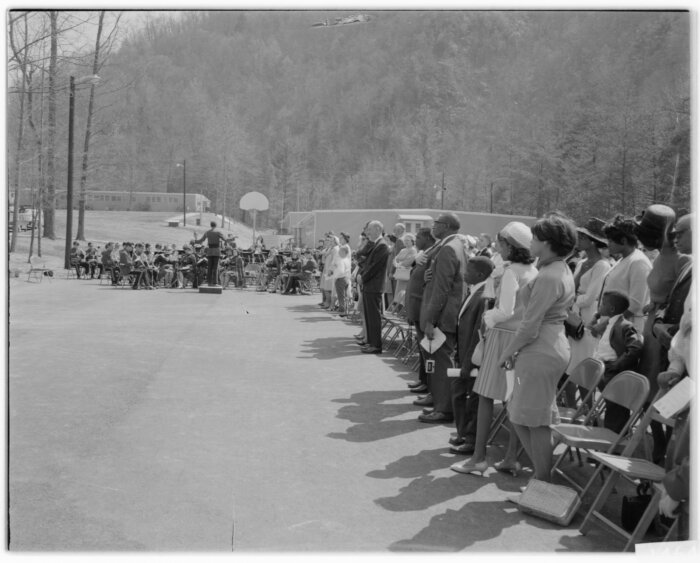

The photo at the top of the page is of Fletcher giving a presentation in Elkmont about the project and the process of creating wayside panels. Such presentations are one way of sharing the experiences of African Americans in the Smokies.

Other outreach initiatives include Park websites — African American Stories and the Black Voices in Appalachia Project.

Friends of the Smokies is helping fund the new interpretive panels and other parts of the African Americans in the Smokies project.