Friend of the Smokies Dee Mason shared with us a story that she wrote for her three grandchildren about a special day they spent in the Smokies back in 2010. The story was so cute, we wanted to share it with everyone. Catch more of Dee’s writing and learn about her love affair with the Smokies in our Spring 2013 issue of ShaConage, our print newsletter.

In search of the wild salamander

Sunday, September 26, 2010

On Friday, we had the opportunity to go to the Ranger Education Center at a place called Purchase Knob in the Great Smokies National Park. A ranger biologist named Susan Sachs taught us how to search for salamanders, and how to gather data on them when we found them. This is something she and other rangers do with mostly highschool students during the months of August through October.

Why salamanders? The Great Smokies has more varieties of salamanders than anywhere else on earth. Some are quite tiny, and one variety grows to 3 feet in length! (Thank goodness, we didn’t find him.)

First, we went out to an area in the woods that is the “classroom”; on the ground were circular cross sections of tree trunks, about two inches high and probably 14 inches or so in diameter. These are called “cookies” (for obvious reasons). Each one was numbered; there are something like 48 in all. Each day, the students will look under each cookie to see if they can find a salamander. Before they lift the cookie, they have to be armed with a plastic bag to catch the salamander, because they are fast little creatures!

The first one we lifted had a salamander! Big John was the one who got to scoop him into the plastic bag. Then Susan the ranger took the temperature of the ground under the cookie, and by using her hand assessed whether it was wet, damp, partially damp, or dry.

Then she looked at the salamander (in the bag) to see what kind it was; the students have an identification guide that helps them tell what kind. Ours was a grey salamander, fairly common; we could tell because it had dainty legs. We then measured it from its snout to the beginning of its tail (still inside the bag).

Once that was done, we weighed it. She had a little scale that looked like a thermometer; she hung the bag from the scale and noted that weight. Then, we let the salamander go by gently placing it beside the cookie. One second, and it was gone-back under the cookie or into the ground. Salamanders are very territorial. If we had put him down farther away, he might have had to fight to gain his cookie back from another salamander!

Then, of course, you’ve guessed the next step–we had to weigh the plastic bag, and subtract that weight from the total weight of the bag and the salamander. Believe it or not, the little plastic bag weighed more than the salamander!

And then it was on to the next cookie–and the next salamander; we did the same procedure for that one as well. The students who had been there that morning had found 38 salamanders in all, some of them by looking under cookies and some by just looking under leaves or logs.

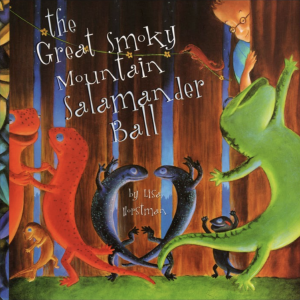

Seems those little creatures are everywhere. They are particularly active at night; sometimes the rangers will go out with flashlights and see them everywhere. Someone even wrote a book for kids called “The Great Smoky Mountains Salamander Ball”!

Seems those little creatures are everywhere. They are particularly active at night; sometimes the rangers will go out with flashlights and see them everywhere. Someone even wrote a book for kids called “The Great Smoky Mountains Salamander Ball”!

No one knows how they travel, whether they go underground and tunnel or go just under the surface of the leaves.

The rangers may have measured the same salamander under the same cookie; they don’t know because there’s no way to tag them. Susan is pretty familiar with them however, and says she thinks they are different. She turned one over in the bag and showed us its heart beating. Very visible!

There are biologists who spend entire careers studying the salamander. One of the things they are looking for is to figure out how the salamanders are adapting to climate change. They like a moist environment, as they breathe through their skin. Keep them dry too long, and they’ll die. So as there is less rain, and the ground gets drier, will they move to a higher elevation seeking more moisture? Will they go farther underground?

Susan always challenges the students to see how many salamanders they can find and enter into the data logs. The students love the work, and over the years the education center has amassed quite a lot of data to analyze.

It was a great experience and pretty amazing to see how they go about their work.

Our encounter with a raging bull (elk)

But perhaps the highlight of our trip to the Smokies was our encounter with a bull elk.

A few years ago, the Friends of the Smokies raised a lot of money to reintroduce the elk

species into the Park. Many years ago, the elk had lived there, but they had been hunted to extinction.

The scientists in charge of the reintroduction had to find another variety of elk in another region that they thought would adapt to the conditions in the Smokies, as the Smokies’ elk were long gone.

They brought them in from out West, tagged each of them with ear tags, kept them in enclosed areas for about a year to see how they would do, and then set them free into the park.

The good news is, they have done beautifully! The herd has grown, and they have remained healthy.

An unexpected bonus of this introduction of the elk herd has been the hundreds of people who come every evening around dusk to watch the elk come out into the pasture to feed. The elk are particularly active right now because it is mating season, and the male elk are gathering their herds of cows. You will see a gathering of maybe 8-10 elk together in one pasture. There will be one bull elk (sporting a huge rack of antlers), several cows, a number of babies from this year’s calving, and some younger male elk.

When we got to the meadow, there had just been a battle between two of the male elks that was apparently quite fierce with lots of clashing of antlers and snorting around. One of the two had been defeated, and had slunk off into the woods beside an old chapel to lick his wounds (mostly his wounded pride). The other male was “bugling,” a curious, high sound which says, “I’m the King and you’re not.” It’s almost like a high trumpet note that keeps going up and up. He uses this sound to keep his herd together.

As we were standing near the old chapel, which was separated from this particular herd by a creek, one of the cows attempted to make a run for it, splashing through the creek in the direction of the defeated bull elk who was in the woods on the other side of the chapel. As luck would have it, a rather large tourist with socks and sandals, a wife and a camera stood between her and the elk. He was trying to take pictures of the sulking elk.

The dominant male elk, seeing the cow making a break for it, charged after her — right toward the rather large tourist, who ran toward the Chapel, where the rest of us were also heading….as fast as we could.

The rampaging bull elk was about 15 yards from us, and cutting off the escape route of the tourist!!! We all piled into the Chapel, where we huddled together until a ranger came and chased off the bull elk. (The ranger later told us that he was prepared to climb a tree if things had gone badly. Apparently, the elk are quite unpredictable this time of year.)

Anyhow, all ended well….the cow went meekly back to her place…the bull elk bugled a little more, and the sullen, sulking elk continued to hide in the woods. The ranger closed off the area due to “aggressive behavior” (not sure if he meant the elk or the tourist) and we were all routed out of there. The rather large tourist has a great story to tell of his time in the Smokies, and I have a story to tell my grandchildren!

Dee Mason is the wife of Friends of the Smokies’ Board Member John Mason. They reside in Asheville, NC.