by Julie Dodd

The Walker Sisters remind us during Women’s History Month of the challenges for women who lived in the Smokies before electricity, indoor plumbing and telephones.

The Walker Sisters gained notoriety because of their refusal to move from their cabin when the National Park Service bought land in the Smokies in the 1930s to establish Great Smokies Mountains National Park.

The Walker Sisters Cabin now is one of the historical buildings in the Park and is a popular hiking destination.

History of Walker Sisters Cabin

The Walker Sisters’ parents – John Walker and Margaret Jane King Walker — married in 1866 when he returned from fighting for the Union in the Civil War.

In 1872, the couple and their four children moved into the home of Margaret Jane’s mother in Little Greenbrier Cove. Margaret Jane’s father had died in 1859.

Ultimately, the couple had 11 children – seven girls and four boys. In 1877, John Walker added a kitchen and front porch to the house to provide more space.

Over the years, all of the sons and one daughter married and moved.

The six unmarried daughters continued to live in the cabin, working the 122-acre farm and managing the household with their parents.

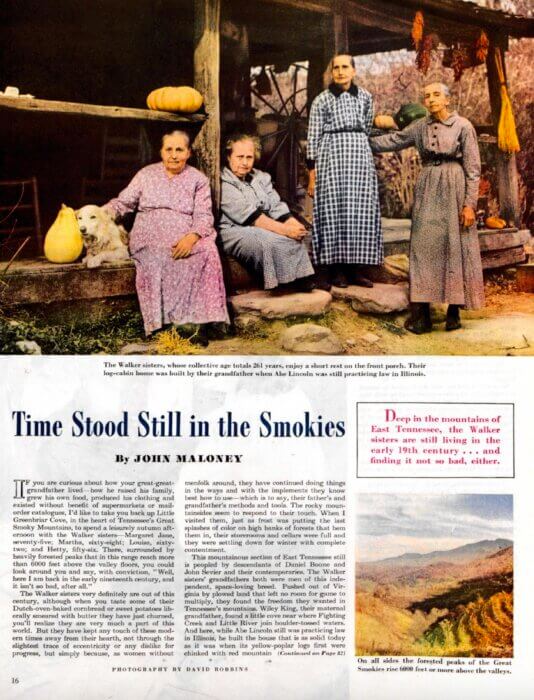

The sisters are pictured at the top of the page — Front (left to right): Margaret, Louisa and Polly. Back (left to right): Hettie, Martha, Nancy and Sarah Caroline (the only sister who married). The photo was taken around 1909.

Margaret Jane King Walker died in 1909. When John Walker died in 1921, the six single sisters inherited the cabin and farm, which they maintained for more than 40 years.

Living the lifestyle of their parents and grandparents

The sisters chose to live the lifestyle of their parents and grandparents, according to Bonnie Trentham Myers, author of The Walker Sisters: Spirited Women of the Smokies.

The sisters grew and raised the food they ate and made their own clothing — without the aid of tractors, sewing machines or refrigerators.

According to the NPS website about the Walker Sisters, the sisters once said, “Our land produces everything we need except sugar, soda, coffee and salt.”

They raised cows, sheep, chickens and hogs and grew corn, wheat, beans, potatoes and other vegetables. They maintained an orchard with more than 100 apple trees and other fruit trees and tended dozens of varieties of flowers, shrubs and herbs. They dealt with their medical needs by using herbal treatments that they learned from their mother.

Creating their own food involved butchering hogs, milking cows, churning butter, and cooking meals over a fire in the fireplace and with a wood stove. Almost every meal included apples they had processed — applesauce, apple jelly, apple pies and apple butter.

The sisters made their clothing, wool blankets, socks and shoes, including shoelaces made from squirrel hides. They used a cotton gin that their father had made and a loom to create cotton textiles. They made wool clothing and blankets from the wool sheared from their sheep. That process involved spinning the wool on a spinning wheel and dying the yarn with berries and tree bark.

Sisters refused to leave their land

The Walker Sisters gained notoriety by standing up to the National Park Service when the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was being created.

When Congress authorized the creation of the park in 1926, the Park Service purchased the land from the families and timber companies, and then the families and companies moved.

The Walker Sisters refused to leave their land.

According to a NPS report (March 3, 1969), a representative of the Washington office of the NPS traveled to the Walker Sisters cabin, in July 1939, to negotiate with the sisters, “trying to talk up a trade with them.” The Walker Sisters “resisted” the NPS efforts to purchase their land, which was appraised in March 1939 for $5,466.

Working with their attorney, the Walker Sisters asked $7,000. In late 1940, the sisters accepted $4,750 (which based on inflation would be worth $93,923 in 2022) for their 122-acre farm and cabin. The agreement included the provision that the sisters were allowed to live on and use the land for their lifetime.

The ownership of the Walker Sisters land passed to the United States on January 22, 1941. Because the Park did not allow hunting, fishing, cutting wood or grazing livestock, the sisters had to adapt their lifestyle.

Another big change for the Walker Sisters happened after The Saturday Evening Post published a story about them in April 1946. The story prompted visitors to seek out the Walker Sisters to see their way of life.

At first the sisters posted a “No Trespassing” sign to discourage visitors. Then they replaced the sign with a “Visitors Welcome” sign when they realized the tourists could help supplement their income. The sisters sold fried apple pies, crocheted dolies, children’s toys that they made and Louisa’s hand-written poems.

In January 1953, Margaret, who was 82, and Louisa, who was 70, were the only two surviving sisters of the six who had lived their lives at the cabin. According to Myers’ book, the two sisters asked the park superintendent to remove the sign on Highway 73 directing tourists to their home. The sisters said they were too old to do all the work of the farm and also entertain visitors.

Margaret died in 1962, and Louisa died in 1964. The Park then took possession of the cabin and the farm.

The lives of the Walker Sisters are a reminder of the hard work and resourcefulness of the women who lived in the Smokies.

Hike to the Walker Sisters Cabin

You can reach the Walker Sisters Cabin by hiking 1.4 miles on the Little Greenbrier and Little Brier Gap trails, starting from near from the Metcalf Bottoms Picnic Area.

You can see the cabin and explore the area and the corn crib and springhouse. The cabin was closed in fall 2021 for major repairs — stabilizing the house’s foundation and fireplace and replaying the roof. The repairs are being made during 2022.

Friends of the Smokies is funding the critical repair work as part of FOTS Forever Places campaign to protect and preserve the Park’s historical resources.

If you’d like to learn more about the Walker Sisters, Bonnie Trentham Myers’ The Walker Sisters: Spirited Women of the Smokies is a great resource. Myers was born about a quarter mile from the Sugarlands Visitors Center before the park was created. Myers’ mother, as a child, often visited the Walker Sisters. Myers visited the sisters in 1947.

“Walker Sisters Home: Historic Structures Report Part II and Furnishing Study” (NPS Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, March 3, 1969) provides an interesting account of the Walker family, the lifestyle of the Walker Sisters, the process of the government acquisition of the Walker Sisters Cabin and farm, and correspondence between the Walker Sisters and the GSMNP superintendent. The report also includes diagrams and photographs of the Walker Sisters, photographs of the cabin and other farm buildings, a list of “Pioneer Culture Items Acquired from Heirs of Walker Sisters.” The report also includes NPS architectural diagrams for restoring the buildings. Robert R. Madden wrote the Historic Structures Reporting, and T. Russell Jones wrote the Architectural Data Section.

A special thank you to Michael Aday, librarian-archivist at the GSMNP Collections Preservation Center, for providing the archived photographs.